thinking about sophistry

carnival, shakespeare, plato

It is winter, cold, and the beginning of carnival season, which properly speaking begins with January 6th’s Epiphany and only gets better/worse until Ash Wednesday. This is not the season, properly understood, of light deprivation and self-murderous valentine discourses, but of carefully fostered hilarity, carefully paced over many weeks. I think it is what people want from summer, or perhaps halloween, and each year they are disappointed, because they do not know what they want, or where in the patterns of the year they most require a time when down can be up.

This is a pity, but not an irrevocable one. Knowing the year can be taught, which is what festivals are for in the first place, bonne fête! It is better for you than the work week or the news cycle, which though they are real and require a certain attention, are of themselves an overlay on the more real thing, which for now, is the reversals of order known as carnival time.

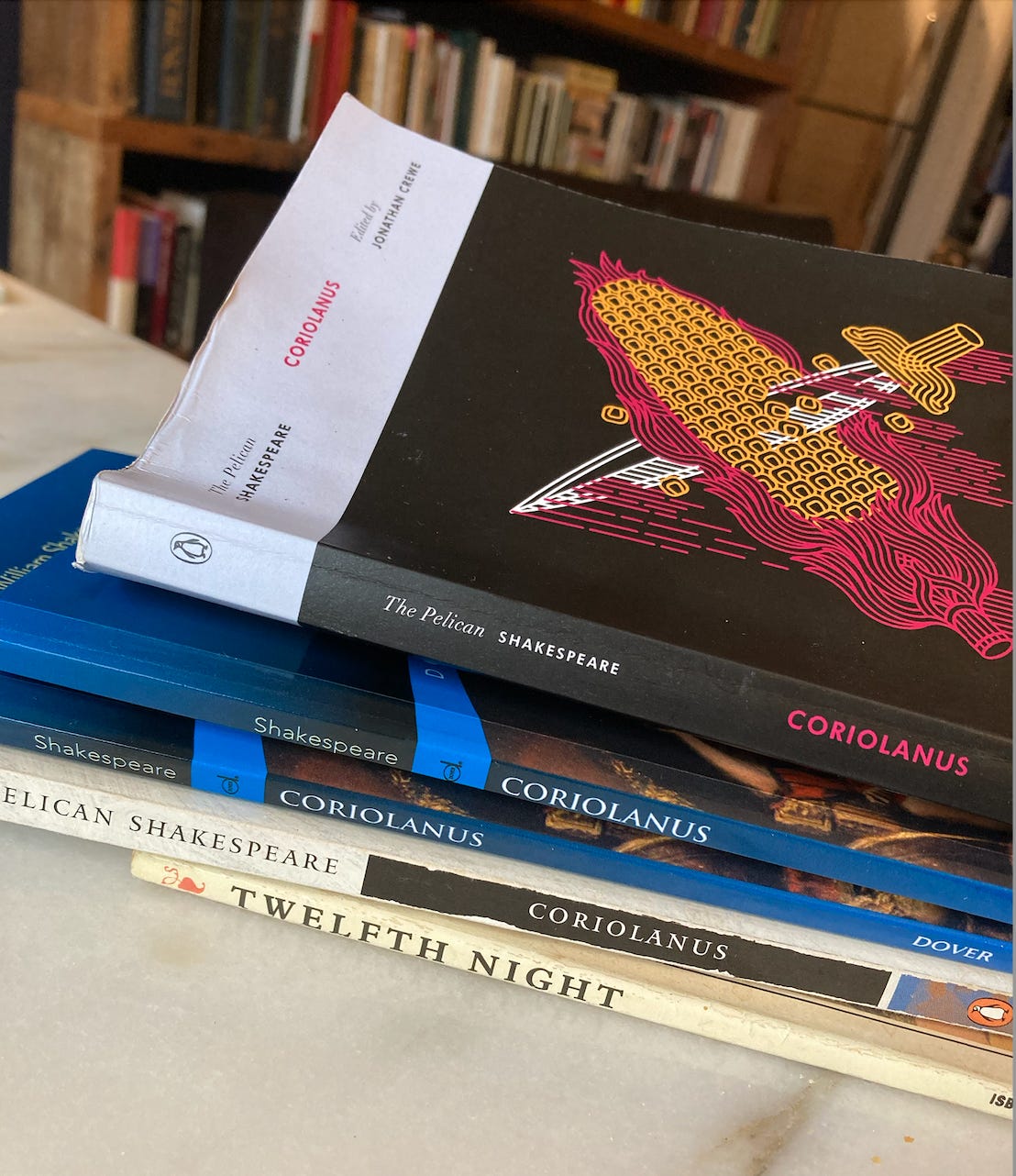

My carnival this year started strong, and now is in a quandry. A week ago I was in France at the theater, then I was in New York, judiciously egging on my guests to read through Shakespeare’s Coriolanus on January 6th. The play describes a roman man who is egged on to try to destroy his own capital city, in this case rome, but you see the point. My guests rather fearfully wanted to know my design here, beyond just the first joke of it. Mainly it seemed important to reclaim Epiphany from bad political actors, with their moose fur and extraordinarily goofy reasons for regime-murder, a bad joke if ever there was one. But in carnival, the way to restore order is not to clamp down on it peculiarly unhumorous fashion. Rather, it’s to seek just where the ordinary order of the polis chafes the most, and then, see what happens if you joke and play around and even play act a bit with a reversal of it without knowing where the chips will land. Carnival is also the opposite of the aestheticization of violence as the first principle of order, and I think, may have the power precisely to heal this rotten sort of instinct, you be the judge.

The play was perfect. It’s one of the harder ones to read, but my guests did it in style, and the peculiar tug when you see the play take shape past any particular reading ability is a beautiful one, every time. Volumnia, the mother who eggs her son on to military virtue, only to realize she has precisely failed to teach him the first thing about statesmanship, was perhaps too good a role for carnival-me. It was enjoyed thoroughly.

Then the next day, it was time for a temporary order, however. I began teaching my class on Plato’s Protagoras, starting off with just the first ten pages or so, to see what was on everyone’s mind. Injustice, of course, whether it is lawful and licit to practice it, or perhaps just a light amateurish smattering, or whether it is rather more serious business. But what was not clear was what injustice had to do with being a sophist, the ostensible subject of the dialogue. Plato is a remarkable author, because no matter how much you think you can walk in to the text, get what you want, and go, one always becomes wrapped into the reversals of the text just enough, that you start having a slightly different argument than the one you thought you showed up for. People find these reversals alarming, off-putting, misology-making. But it is possible to learn to enjoy them—as long as you make up your mind in advance, that you too will never safely escape.

Here in the Protagoras, the interesting shift is that, while students show up to Protagoras because this whiff of glamour that surrounds him, is, without him ever saying so, does bear a certain relation to some sort of injustice, where it might become licit to say that injustice, at least the sort that benefits you, is licit. It is almost as if the reader is looking for Protagoras’ blessing, in some odd way, just for the relief of having it; and that is most certainly what he ever so glamorously intends for you to understand that he is selling, and that you can buy. The difficulty is, what Protagoras claims to teach is not the manner of doing injustice, in the hard details of it; he is no Machiavelli, who deeply wishes that, if you claim you are interested in injustice you should be willing to work quite hard at not being deeply stupid. Indeed, Protagoras explicitly advertises that his sort of teaching will not be hard, that it won’t require learning anything except precisely that which you already want (317d). He is telling precisely the truth.

This sort of truth-telling which is flattery itself, the glamour, the intellectualism, the slightly jaded sense that all has already been written down somewhere, the complicated subterfuges that nevertheless are meant to be explicit enough, all of this makes some small part of the phenomenon of the sophist, that tricksy character, who is always one step ahead of any definition we might care to claim. Sophistry is not something that is always in politics, but when it gets rooted down in it, it becomes peculiarly difficult to see, and it is one of the human things that is most real in the world that, like Eros, without Plato’s work we might never have simply seen; each of these in all their complexity, might simply have escaped the notice of humankind, forever, and so much the worse for us.

The possibilities inherent in sophistry, that unlike some simple lie or deception that is neatly opposed to some equally simply truth, can sit right in the flattering space between appearance and being, always with just enough truth to satisfy what we most of all would be glad to purchase and feel quite grateful so to do, are endless, even if they are anything but practical. It’s like a luxury good you want someone to talk you into thinking is a necessity, or as Socrates puts it, fancy makeup.

Rhetoric, by contrast, can and does have a much more concrete and practical aim, it deals in specific outcomes, it is more like a judgment about a thing, and while Socrates is right that it arises via a certain kind of experience and the scratching of an itch1, it does have redeemable and at least partly learnable characteristics; and it is probably not possible to have any sort of politics or education without it, for better or worse. But sophistry is different, and weirder, because it appears to be about architectonic things, not the judgment or the practice but the universal, the schema, and the blessing of the schema, and often looks to us much more like the philosophy we want, than whatever else philosophy itself might be.

But so here is my carnival, and here’s what I am trying to catch sight of yet. Sophistry can equally flatter our desire for goodness, no less than the desire for anything else. Divorced from injustice, is it even interesting or fun to look at for its own sake, and what would it take to show it to be so? Injustice is sophistry’s own kind of cloak, just another way it has of getting paid, and if you really want practical advice on taking over a small italian town, you’d do better elsewhere—yet the practical truth is that Machiavelli was exiled, and Protagoras went where he pleased.2 Where in all this is the pedagogical reversal I need, to turn the interest away from the vaguest, goofiest kinds of injustice, away from the strange dream that fun chaotic bits of injustice will immediately win you power and glory, rather than irreparably wrecking the body politic and showing you to be an ass? And towards what? Let us hope, towards an order that is more than humorless. In Plato’s carnival, surely the possibility of this reversal is always present, even if what happens next remains inevitably unpredictable. Onward to better carnival wisdom for the soul!

“Knack” is still my favorite translation of τριβή from the Gorgias here, but rubbing, as in the way Socrates rubs his foot at Phaedo 60b, or the way time wears something away as at Republic 6.493b.

And Plato . . . is banned . . . in Texas, is that the news?