Le rayon vert

chapter 1

Bet!

Beth!

Bess!

Betsy !

BETTY !

Such were the names that resounded successively in the superb hall of Helensburgh, —the fashion of brother Sam and brother Sib to seek for the woman in charge of the house.

But, this time, these friendly diminutives of the name Elizabeth did not produce the excellent woman in question, any more than if her masters had called out her name entire.

It was the attendant Partridge, in person, who appeared, hat in hand, at the door to the hall.

Partridge addressed himself to two personages of goodly mien, seated in the opening of a bay window, whose three diamond-shaped glass panes made an alcove set just past the house’s façade.

“Sirs have called for dame Bess, but dame Bess is not in the house.”

“Where is she then, Partridge?”

“She accompanies Miss Campbell, who rides in the park.”

And Partridge retired gravely at a sign made to him by the two.

These were the brothers Sam and Sib—their true baptismal names being Samuel and Sebastian—the uncles of Miss Campbell. Scotsmen of the true old heath, Scotsmen of an ancient Highland clan, adding together they could count up one hundred and twelve years of age, with only fifteen months’ space between the elder brother Sam and the younger Sib.

To sketch, as it were, these prototypes of honor, of courtliness, of devotion, it suffices to say that the entirety of their existence was consecrated to their niece. They were the brothers of her mother, who, made a widow after the first year of her marriage, was herself soon carried off by a strikingly sudden illness. Sam and Sib Melvill remained therefore the sole guardians, in this world, of the small orphan. United in the same tenderness, they lived, thought, and dreamed for naught but her.

It was for her that they remained bachelors, without regret, moreover, and for her they were these good souls, who had no other earthly role to play besides that of her tutor. And even that is not enough to say: the elder was as father, and the younger, as the mother of the child. Thus on occasion, it was only natural for Miss Campbell to greet them with, “Good morning, papa Sam! How do you do, mother Sib?”

With whom could one better compare them, saving the practical side, if it were not to the two charitable merchants, so good, so united, so affectionate, the brothers Cheeryble of the city of London, the most perfect beings ever to spring from the imagination of Dickens? It would be impossible to find a more just resemblance, and, should any be tempted to accuse the author of having lifted their type from his masterpiece Nicholas Nickleby, no one could regret the transposition.

Sam and Sib Melvill, allied by the marriage of their sister to a collateral branch of the ancient Campbell family, had never left the other’s side. The same education had made them alike in character. They had received together the same instruction in the same college in the same class. Thus from them emitted generally the same ideas on all things, in identical terms, the one always able to finish the phrase of the other, with the same expressions emphasized by the same gestures. In sum, the two beings were as one, although there was some difference in their physical constitution. Indeed, Sam was a little more tall than Sib, and Sib a bit fatter: but they could have exchanged their gray hairs, without altering the character of their honest figures, where was found the imprint of all the nobility of the descendants of the Melvill clan.

Need it be added, that in the cut of their clothes, simple and of the old-fashioned mode, in the choice of their good English cloth, they displayed a similar taste, if it were not that—who could explain this slight difference—if it were not that Sam seemed to prefer a dark blue, and Sib, a somber brown?

In truth, who would not have wished to live in imitation of these dignified gentlemen? Habitually walking with the same step, they will stop, without a doubt, at but a small distance from the other, when the hour of their final halt will come. In any case, the two last pillars of the house of Melvill were firm. They must support for a long time yet, the ancient edifice of their family, which dated from the 14th century—the grand times of Robert Bruce and Wallace, that heroic period, when Scotland vied with England for their rights of independence.

But if Sam and Sib Melvill did not have any longer the occasion to fight for the good of their country, if their life, less disturbed, had passed in the calm and ease made by good fortune, it is not necessary to blame them, nor to believe them soft. They had, in doing good, continued the generous traditions of their ancestors.

Likewise, both in good health, there was not a single irregularity of existence to reproach them with, and they were destined to age, without every having become old, either in spirit or in body.

Perhaps they had one fault—who is able to flatter themself on being perfect? It was to interlace their conversation with images and references borrowed from the celebrated chatelain of Abbotsford, and more particularly, with the epic poems of Ossian, on whom they doted. But who could find fault with that, in the country of Fingal and Walter Scott?

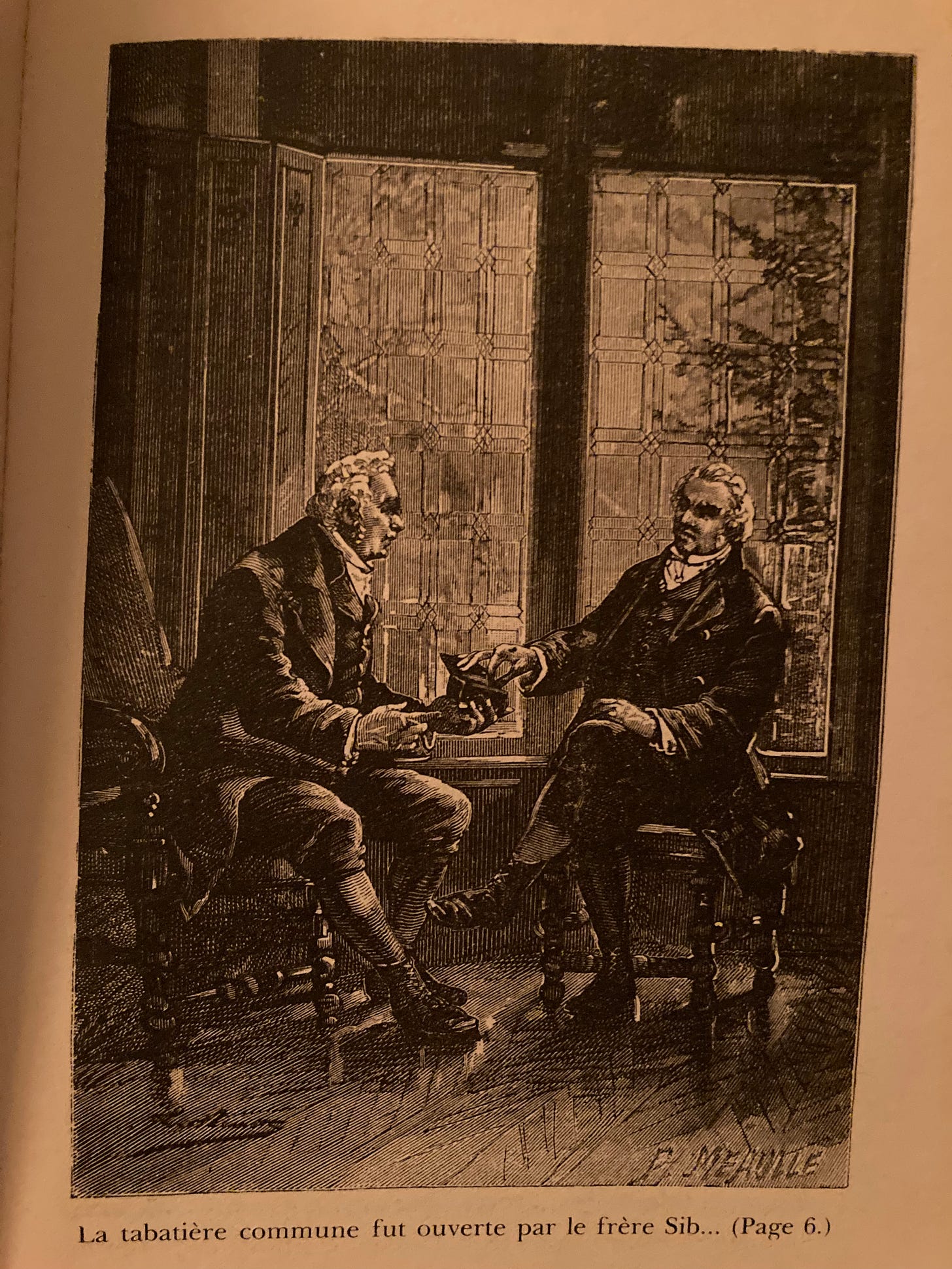

To conclude their indictment with a final touch, it must be noted that they were great smokers. Or rather, no one could fail to recall the well-known signage of the tobacco merchants of the United Kingdom, wherein is usually displayed a valiant Scot, snuffbox in hand, proudly attired in traditional costume. Well, the brothers Melvill would have certainly shown to advantage on one of these painted zinc panels, creaking in the wind at the shops. They prized tobacco as much or more as anyone, on either side of the Tweed. But, in characteristic detail, they only had one snuffbox between them; to illustrate, a quite large one. This portable furniture as it were, passed successively from the pocket of one to the pocket of the other. It was yet another line between them. And it goes without saying, that they felt at the same moment, ten times an hour perhaps, the desire to sniff the excellent powder of nicotine they’d had sent from France. When one of them took the snuffbox from the depths of his habiliments, it was that both had the wish for a good pinch; and if one of them sneezed, they would say, “God bless us!”

In sum, two true infants, the brothers Sam and Sib, towards all that concerned the realities of life, and just as little up to date on the practical things of the world; in industrial matters, financial or commercial, absolute zeros, and they did not at all pretend to know anything about it. In politics, perhaps, they were Jacobites at the core, holding on to some prejudices against the reigning dynasty of Hanover, dreaming of the last of the Stuarts, as a Frenchman might dream of the last of the Valois; and lastly, in matters of the heart, still less did they know.

Yet despite this the brothers Melvill had but one idea: to see clearly into the heart of Miss Campbell, to divine her most secret thoughts, to guide them if needed, to develop them if necessary, and finally, to marry her to brave young man of their choice, who could do no otherwise than make her completely happy.

To believe them in this—or rather to hear them speak about it—it appeared that they had found precisely the brave young man, upon whom this amiable task would fall here on earth.

“And so, Helena is out, brother Sib?”

“Yes, brother Sam, but it’s five o’clock, and she can’t be long in returning to the cottage.”

“And once she returns . . . ”

“I think, brother Sam, it will be right to have a very serious talk with her.”

“In just a few weeks, brother Sib, our child will have reached the age of sixteen years.”

“The age of Diana Vernon, brother Sam. And isn’t she just as charming as the adorable heroine of Rob Roy?”

“Yes, brother Sib, and in the grace of her manners . . . ”

“The turn of her spirit . . . ”

“The originality of her ideas . . . ”

“She calls to mind Diana Vernon more than Flora Mac Ivor, that grand, imposing figure from Waverly!”

The brothers Melville, proud of their national author, recited still more of the names of his heroines, from The Antiquary, Guy Mannering, The Abbot, The Monastery, The Fair Maid of Perth, Kenilworth, and so on; but all of these, to their taste, ought to give way before Miss Campbell.

“She is a young rosebush who has shot up rather quick, brother Sib, and for whom one must. . . ”

“ . . . Must offer a tutor, brother Sam. However, I give myself leave to say, that the best of all tutors . . .”

“. . . ought evidently to be a spouse, brother Sib, for it takes root in the same soil . . . ”

“. . . and grows up so naturally, brother Sam, with the young rose it protects!”

This pair, the brother-uncles Melvill, had found and stolen this metaphor from The Perfect Gardener. Without a doubt, they were satisfied with it, for it brought the same smile of contentment upon their goodly mien. The shared snuffbox was opened by the brother Sib, who carefully poked two fingers into it; then the box passed to the hand of brother Sam, who, after taking a large pinch, put it in his pocket.

“And so, we are in accord, brother Sam?”

“As always, brother Sib!”

“And in the choice of the tutor?”

“Could it be possible to find someone more sympathetic or of a good will for Helena than this young savant, who, so often, has shown us such proper feelings that . . . ”

“And so serious in his regard that . . . ”

“It would be quite difficult! Educated, a graduate of the universities of Oxford and Edinburgh . . .”

“A physicist such as Tyndall!”

“A chemist such as Faraday!”

“He knows right to the bottom the reason for all things in this world, brother Sam . . .”

“And one could hardly take him off guard with any sort of question, brother Sib . . . ”

“Descendant of an excellent family, of the Earl of Fife, and furthermore, in possession of sufficient fortune . . .”

“Not to mention his quite agreeable looks, to my eye, even with his aluminum-frame glasses!”

Had the glasses of this hero been of steel, nickel, or even of gold, the brothers Melvill would not have accounted it a prohibitive vice. It is true, this sort of optical apparel does well for young savants, who wish to complement a somewhat serious physiognomy.

But this graduate of the aforementioned universities, this physicist, this chemist, would he be agreeable to Miss Campbell? If Miss Campbell resembled Diana Vernon, Diana Vernon, it is known, evinced no other regard for her brilliant cousin Rashleigh than a mild friendship, and at the end of the book, she married him not.

Well! This, in truth, did not bother the two brothers. They had all the inexperience of two old children, incompetent enough with such materials.

“They have often met, you know, already, and our young friend has not seemed insensible to the beauty of Helena!”

“Well do I believe it, brother Sam! The divine Ossian, if he had had to celebrate her virtues, her beauty and grace, he would have named her Moina, that is to say, ‘beloved of all!’”

“Unless, of course, brother Sib, he’d named her Fiona, that is, the Gaelic nonpareil!”

“And did not he divine our Helena, brother Sam, when he said: ‘Leaving her retirement where secretly she sighed, she appears in all her beauty/as the moon, at the fringe of an Oriental cloud.’”

“‘And the brightness of her charms surrounds her, like rays of light,’ brother Sib, ‘and the sound of her slight steps/meets the ear as does sweet music!’”

Happily, the two brothers, stopping there in their recitations, fell back from the slightly clouded sky of the bards, into the domain of reality.

“To be sure,’ said one, ‘if Helena has pleased our young savant, he cannot fail to please her . . . ”

“And if, on her side, brother Sam, she has not yet accorded him all the attention due to his great qualities, with which he has so liberally been endowed by nature, . . .”

“Brother Sib, it is only because we have not yet told her that it is time to think on being married.”

“But on the day when we guide her thought to this purpose, supposing that she had some aversion, if not to the man, then to marriage— ”

“She will not be slow to say yes, brother Sib . . . ”

“Just as the excellent Benedict, brother Sam, after having resisted a long time . . . ”

“ . . . finished, at the denouement of Much Ado about Nothing, by marrying Beatrice!”

See how they arranged things, the uncles of Miss Campbell, and the resultant of this compound seemed to them as natural as that of the comedy of Shakespeare.

They arose from their seat in common accord, observed each other with a final smile, rubbed their hands together judiciously. It was an affair concluded, this marriage! What difficulty could have arisen? The young man had made his request to them. The young lady would make her response, about which they did not have to worry at all. All the conveniences were there. They had only to fix the date.

In truth, it would be a beautiful ceremony. It would be held in Glasgow. To illustrate, it would in no wise be at the cathedral of St. Mungo, the only cathedral in Scotland, with the cathedral of St. Magnus in Orkney, which the period of Reformation had left intact. No! It was too massive, and in consequence, too gloomy for a marriage, which, in the thinking of the brothers Melvill, ought to be a vortex of youth, a ray-beam of love. One ought to choose rather St. Andrew or St. Enoch, or even St. George, which belonged to the properest part of town.

Brother Sam and brother Sib were continuing to develop their projects in a form which resembled more a monologue than a dialogue, where there was always the same set of ideas, expressed in the same fashion. While talking thus, they observed through the diamond-panes of the vast bay window, the beautiful trees of the park, under which Miss Campbell was riding at that moment, the leafy garden-borders enframing the many streams of rushing water, the sky overfull with a luminous mist, particular to the Highlands of central Scotland. This they did not regard, it would have not been useful, but, from time to time, with a sort of affective instinct, they took each other’s arm, their hands, as though to better establish the communication of their thought, by the medium of a sort of magnetic current.

Yes! It would be superb! All things would go grandly and nobly. The poor of West George Street, if there were any—and when were there not?—they would not be forgotten at the occasion. How, impossibly, Miss Campbell might wish that all would go more simply, and, on this subject, require to be made to see reason by her uncles, her uncles would easily know how to put their foot down for the first time in their life. They would cede neither this point, nor any other. It would be a grand ceremony, where the engagement dinner guests would “drink from the roofbeams” according to the oldest custom. And the right arm of brother Sam was half-stretched out, at the same time as the right arm of brother Sib, as though they exchanged in advance the famous Scottish toast.

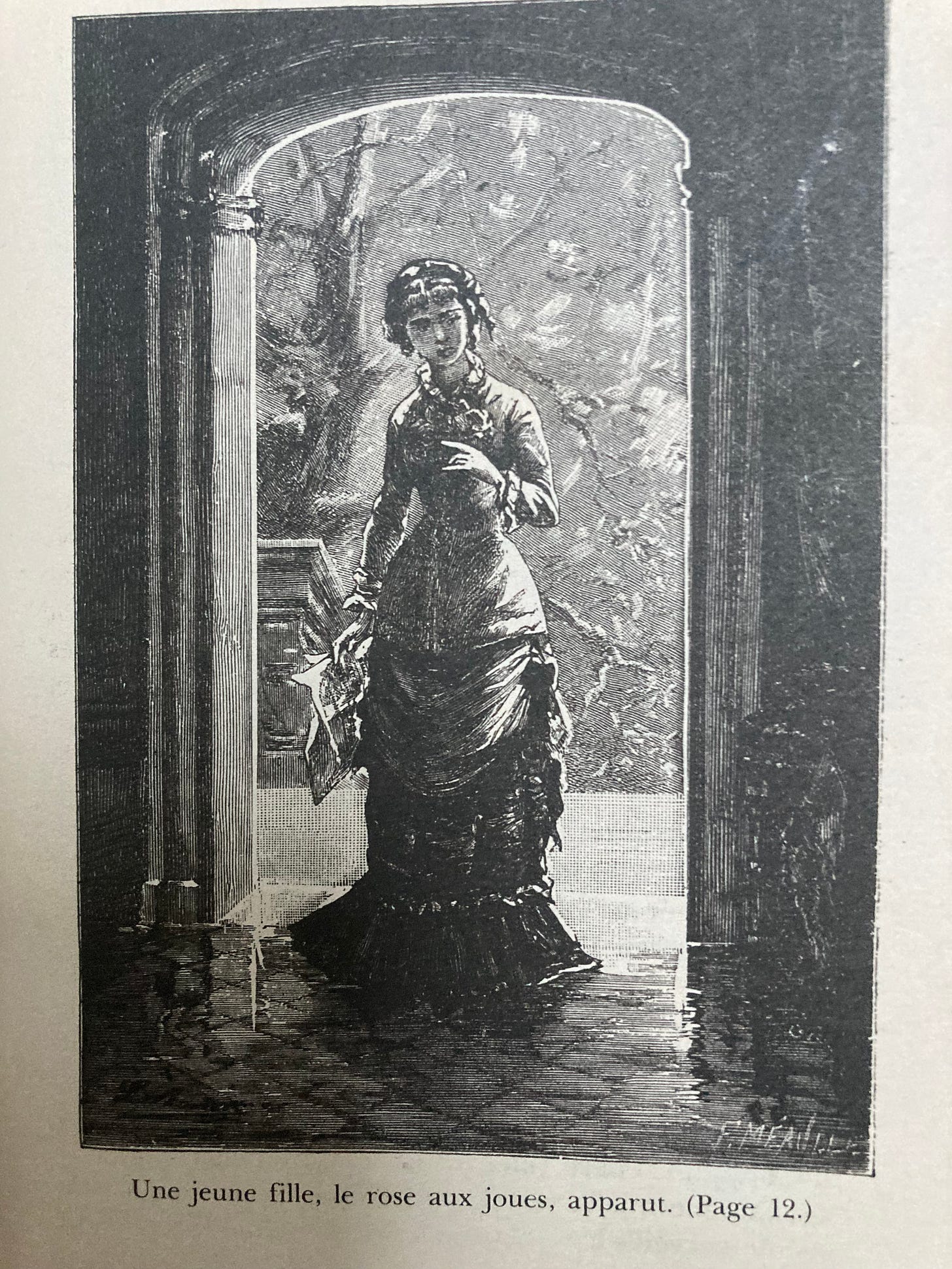

At this instant, the door to the hall opened. A young girl, roses in her cheeks from the animation of a rapid course, appeared. Her hand waved an unfolded newspaper. She directed herself towards the brothers Melvill, and honored them with two kisses for each.

“Greetings, brother Sam,” she said.

“Greetings, my dear child.”

“How goes it, uncle Sib?”

“Excellently well!”

“Helena,” said the brother Sam, “we have a small arrangement to make with you.”

“An arrangement! What arrangement? What have you been plotting, my uncles?” asked Miss Campbell, as her glance, not without some malice, went from one to the other.

“You know that young man, M. Aristobulus Ursiclos?”

“I know him.”

“Do you dislike him?”

“Why would I dislike him, Uncle Sam?”

“Well then, do you like him?”

“Why would I like him, Uncle Sib?”

“Well, my brother and I, after mature reflection, think to propose him to you as a husband.”

“Marriage! Me!” cried Miss Campbell, and let out the most joyous sliver of laughter that the hall’s echoes had ever repeated.

“Do not you wish to be married?” said brother Sam.

“To what end?”

“Never . . . ?” said brother Sib.

“Never,” said Miss Campbell, taking a serious air, which the laughter on her mouth belied, “never, my uncles— at least so long as I have not seen—”

“What, then!” exclaimed brother Sam and brother Sib.

“As long as I have not seen the Green Ray.”

Thanks, all—this is my experiment in tracing back the references in Eric Rohmer’s 1986 film Le rayon vert, named after this 1882 novel by Jules Verne. There’s usually quite a punch to Rohmer’s references, so I am looking forward to seeing how this develops as I translate, chapter by chapter. I’ve been wanting to read this novel for some time, but for whatever reason, had trouble finding a copy in french, let alone english, till I recently came across a paperback by the Seine. I translate a fair amount of Greek, but have never attempted something like this. But in my reading of Verne last summer, I found I preferred the liveliness of the 19th century english translations, while still regretting a certain smoothing-out of the style and meaning, and as is well known, the political meaning, too. So this is my attempt to use some of the verbiage of Trollope, Scott, Wilkie Collins, and all, to keep this story moving apace, and to tease out some of the scientific language, too—the zinc might be my favorite image from this portion. If not the aluminum lunettes. Strong Elective Affinities vibes, too. And how perfectly does this chapter end. I do not know how the story ends, so I will be back to polish the foreshadowing eventually, perhaps. Hope you enjoy, and if you’d like to read on, I will be much encouraged by your encouragement for more!