Looking for context for an insult in Plato, I went looking into Theophrastus yesterday, via a rather extraordinary illustrated edition from 1881.

This is supposed to be the gross guy, the βδελυρός, which is the insult that Thrasymachus attempts to pin on Socrates at Republic 338c-d. There’s an interesting and complicated way it might be fair which I will not explain just at present. However, take a look at a few more of these guys!!

Don’t be looking for ways to pay someone less than you promised for their work in the first place, lest you end up like this guy.

Or!

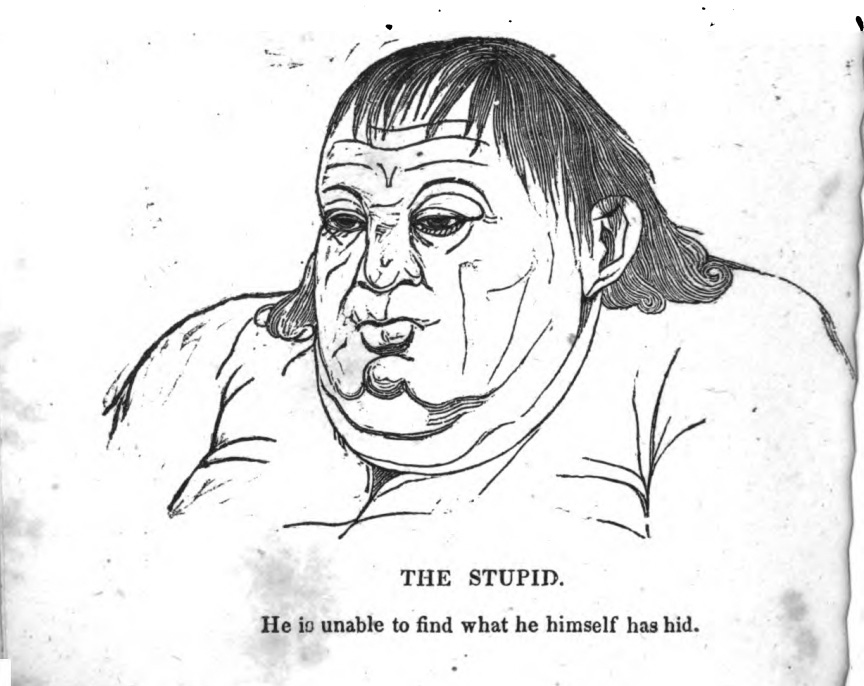

I mean I regularly cannot find what I have hidden. But still.

The descriptions are short and painfully familiar: we know these people, and it’s very funny to see them at it. There’s the “malignant temper venting itself in ferocity of language” where if you accidentally kick a stone you curse it out; the petulant man who finds fault with heaven “not because it rains but because it rains too late;” and the sort of vanity where since “ambition is the ruling passion of a vulgar mind, it shows itself in the eager pursuit of frivolous distinctions” —like apparently, always paying in newly minted coin, or wearing your party clothes all day. (Granted, the vain man’s examples are the least recognizable, since the frivolous things he is interested in are so frivolous and inessential that the distinction he hopes they confer easily passes away with time.)

But the one who caught my attention the most was “the dissembler,” the one who possesses εἰρωνεία. It’s how this translation describes the ironist, which is a reasonable way to narrow the specifics of what is being described here. In Theophrastus’ version, this person isn’t quite the ironist Kierkegaard describes in Concept of Irony, who enjoys staying suspended on the edge of meaning for the joy of it; rather, the dissembler has a sharp ulterior motive for always distancing himself from a promise, a meaning, a through-line, even his own projects—some advantage he seeks for something or other.

Like ordinary untruthful people, the dissembler flatters people he wants to thwart, pretends to be friends with an enemy. But then it gets more complicated: He “feigns not to have attended to what he heard, he professes not to have observed what passed before his eyes, and he takes care to forget his promises.” Working this hard at all times for distance seems less about a specific motive, and it’s almost as though there might be some enjoyment in the suspension for its own sake after all.

Consider:

I really like the description of the person who at one moment exactly agrees with you, and the next, can’t believe you just said that. “I don’t take your meaning, sorry!” It’s as if he’s making use of the infinity of language to elude the world, but for the pettiest of motives, some advantage so small he’s forgotten what it is: “prithee find some one else to whom you may tell this tale—I am not the man you take me for.”

Socrates would never!