Iris Murdoch in the Woods

second summer book; family death.

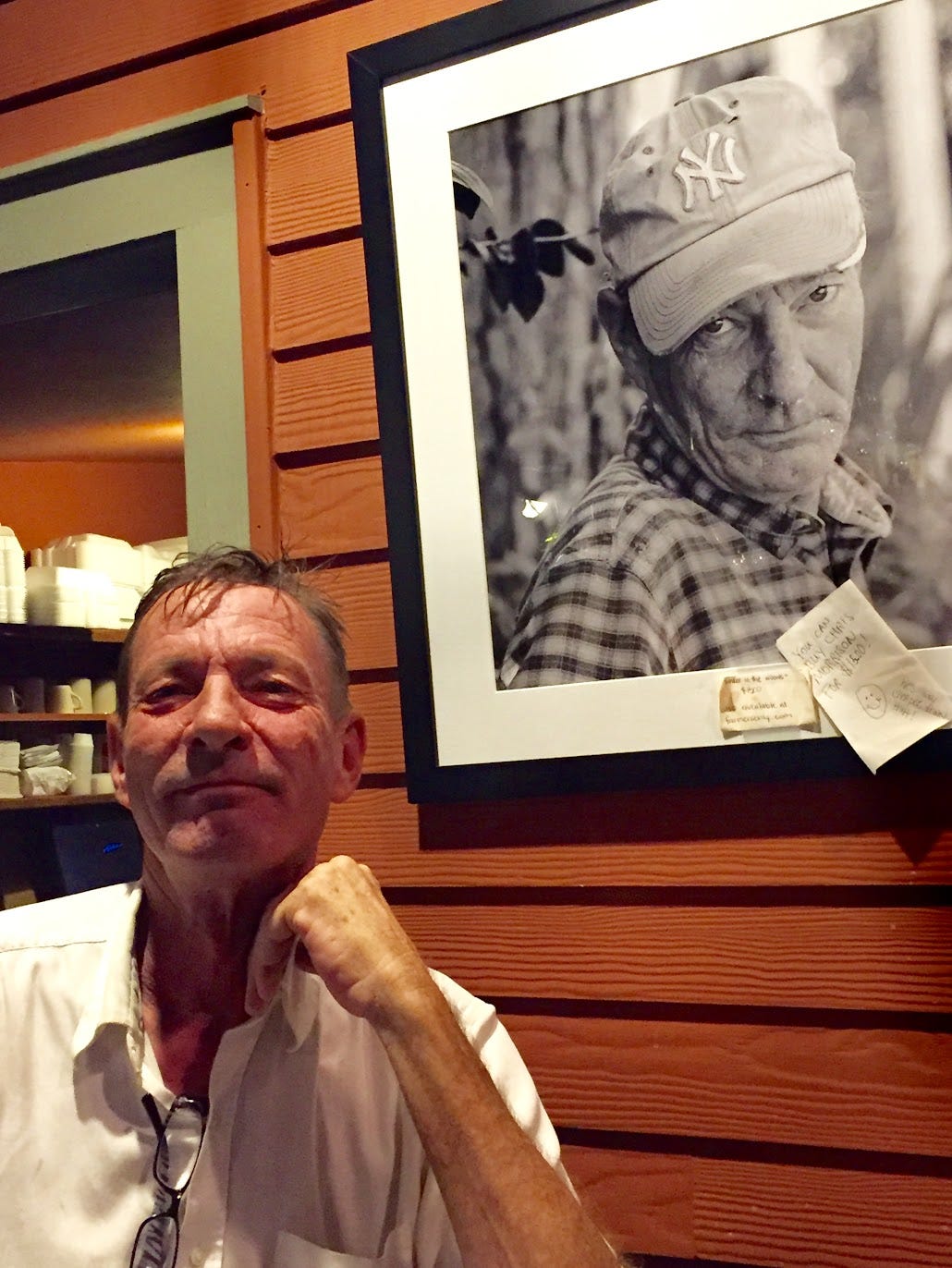

My dear uncle Chris, Christian Seghers Morrison, pride of St. Francisville, LA, let us call him the scourge of Rod Dreher, died about two months ago during heart surgery. He was 66.

My large extended Southern Catholic family usually gets together for the 4th of July for a big party in central Louisiana, in the woods. It took me a few extra decades to realize the date of this had silently also commemorated the death of an uncle I never met, Chris’ slightly older brother, who died around the 4th when he was quite young. In my family, we know the southern gothic by heart; and I don’t think any one of us had a keener sense of this than Chris. Listening to him talk in and around this when I was young is probably one of the sharpest reasons that when I first picked up Greek tragedy as a teen, it felt like coming home.

photo credit: Paul Kirkland

After the monkish interlude I spent in Maine and Boston, I flew to Dallas and drove to points slightly north of Alexandria, LA, glad that I’d already made plans to get to the Dionysian family party, because now the party was going to be for mourning too; which I knew we’d do well, from practice. Well, and for talking in public, what can one do but praise the woods and acknowledge the death; remember to send a prayer and ask for one, too. I’ll miss Chris for a long time, and a lot of people I love will miss him even more.

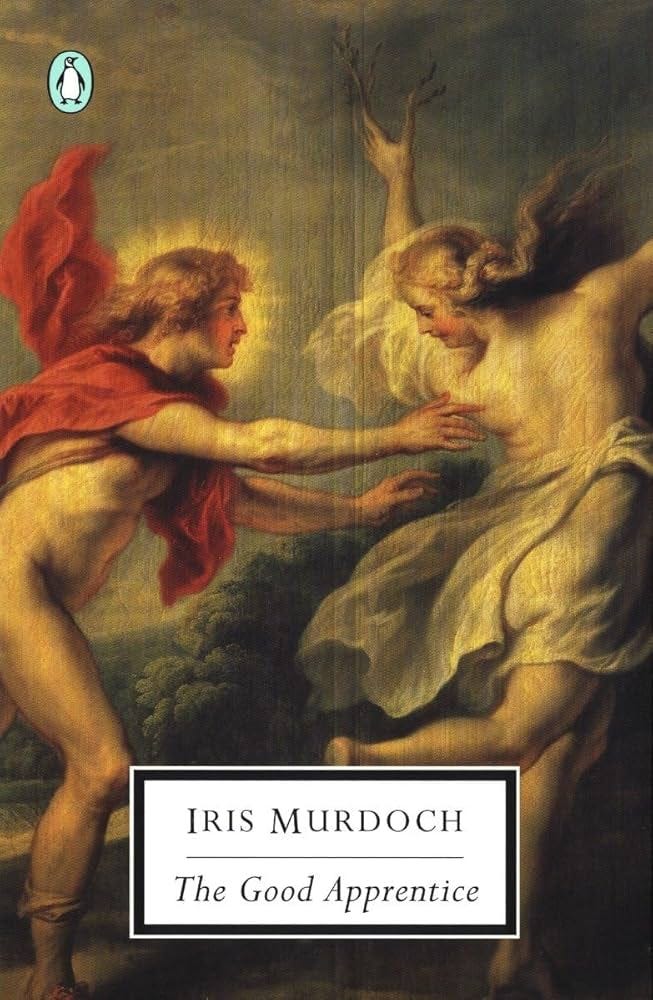

In this context did I, a trepidatious reader, pick up Iris Murdoch’s The Good Apprentice, one of her later books but not too late, and read it all through, finishing it the night before I left again from Dallas to further thoughts and people. I love Iris Murdoch for many reasons, though for me she was an acquired taste; after a few practice novelic experiences with her, however, I got into the habit of trusting her to help with a certain kind of catharsis. My rule for a newly-picked-up book from her is that I go to a used bookstore and if they have one I haven’t read it I can read that one. I look under very specific circumstances, usually at large endings, almost always in may or june, both for the large ending of academic year frustrations, and for this year, for even something beyond what I could well understand. In this as I hoped, she did not disappoint.

The Good Apprentice starts with a murder. Page one, don’t worry. But right away you know you’re in for it, because when murder is not denouement but the occasion for a story, that’s when gothic really begins. The novel was a lovely blend of the usual horrific adulterous aging successful unsatisfied british people in the 1980s, as one expects (The Severed Head, Henry and Cato, etc.); but this time cut with some of the nicest other Murdoch things: what one sees in The Unicorn, that is, people living apart in strange houses sustained by something other than semi-public intellectual life, though quite unaware of what that entails for others beyond the strange house’s bounds; and also skimming towards the edges of the fantastic like the end of The Sea, The Sea and the glorious end of the bathhouse fabula The Philosopher’s Pupil; at one point, one of the characters dances on air. (in the woods.) It did not make me feel better. But it did put me in the middle of other people’s problems, helpfully, in a way that I can record mainly through the sense of color: red orange, and occasionally dusk, and a sense of constant falling away, like when one awakes from a dream of falling through space; ever so slightly contained by art, and dark but not unbenign places.

The novel ends without a resolution: the accidental murderer is still haunted by the death he partly caused, the adulterous aging successful unsatisfied british people are only partly mollified; the william morris inspired incestuous subplot falls straight into an unredeemed—and I mean really unredeemed, burlesque hell. But there were enough clouds of identified-enough rampant feelings that a favorite quotation from Sovereignty of Good, the one that names human consciousness as: “a cloud of more or less fantastic reverie designed to protect the psyche from pain,” held good. And as the murder-narrator puts the corollary to this, in his slowly almost-clarifying reverie, perhaps some experiences are simply eternal: one doesn’t move on, move through, there’s not a way to digest: that’s the wrong metaphor.

But the experience of experiencing timelessness isn’t just our moments of noetic insight; it’s also the slow discovery of ways to live with what’s already terrifyingly timeless, like someone else’s death always will be. To live again without becoming, as in a 13th century painting, the small minor character drawn carefully in the corner, always in the shock of experiencing the same moment, again. Timelessness is almost but not always too real for our psyches; few authors or family members could have been a better friend to seeing that, again.

Goodbye, my dear uncle; I will see you again.

I’m sorry for your loss, my friend. I’ll say the mass for Christian Seghers Morrison today.

"To live again without becoming, as in a 13th century painting, the small minor character drawn carefully in the corner, always in the shock of experiencing the same moment, again."

Perfect.

Sing on!